In my final trip into Washington, DC, last month before our move, I visited a place that’s been on my bucket list—the Victims of Communism Museum. The museum opened three years ago and it’s located in an old, marbled office building a few blocks northeast of the White House. I spent an engrossing if somber two hours there viewing the exhibits dedicated to preserving public memory of the century of horrors visited on humanity by communist ideology.

The museum features panel displays with key facts about the origins and the bloody and oppressive record of communism—not only in Russia, but in Poland, Ukraine, the Baltic Republics, China, North Korea, and Cuba. Short videos throughout the museum show interviews and historical film footage. One hallway displays photos and short biographies of East Germans who died between 1961 and 1989 while trying to get around the Berlin Wall to freedom.

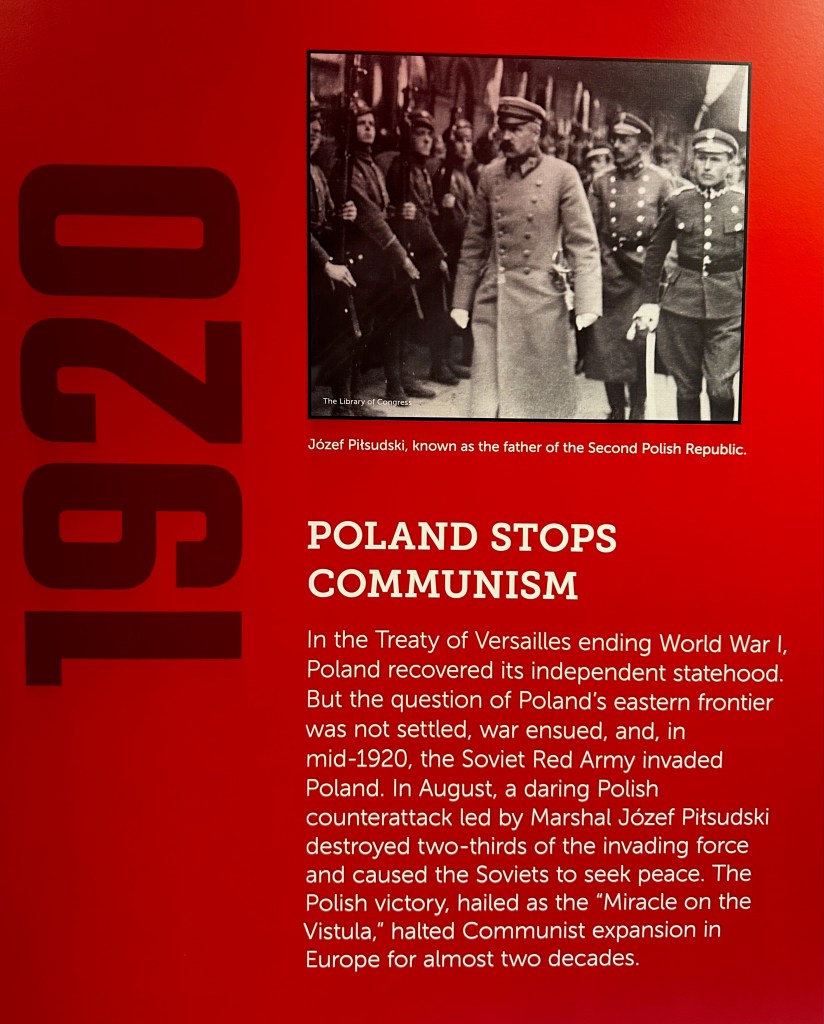

Among the interesting facts I learned is that in 1920 a newly independent Poland repelled an invasion by the Red Army. The military victory under Marshal Józef Pitsudski secured Poland another two decades of freedom before being carved up again by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union in 1939. One more reason to admire the Poles!

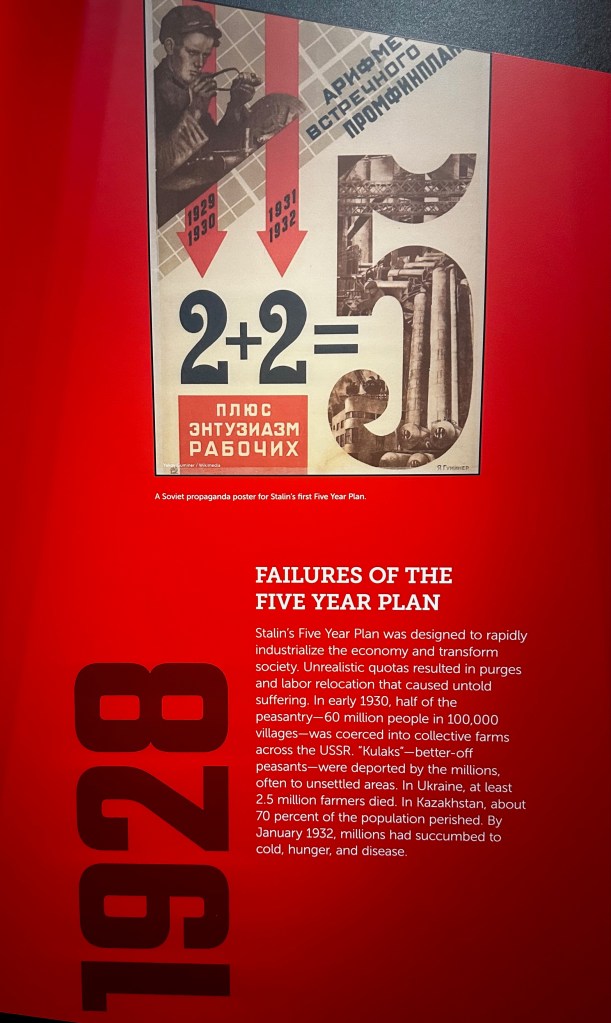

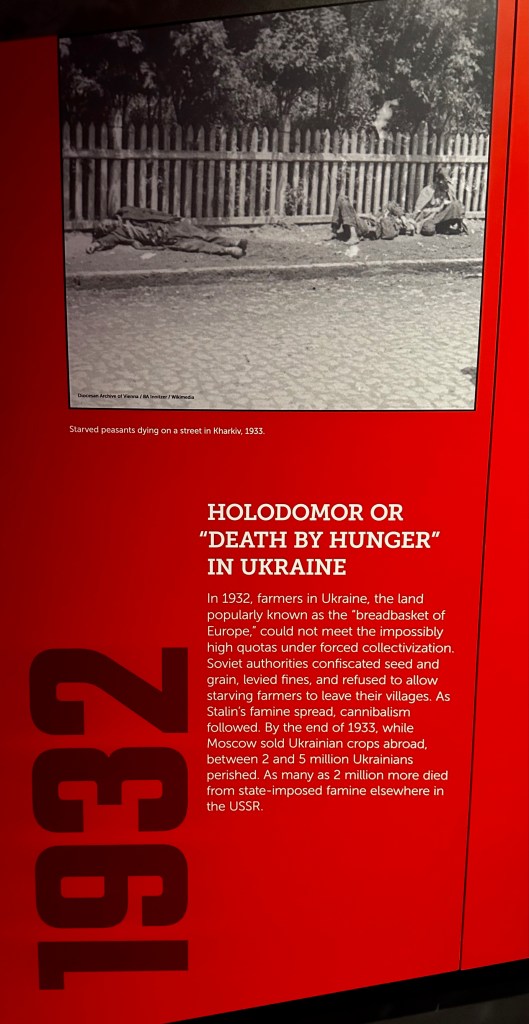

Here are some of the panels at the museum that I found most informative:

At the heart of the museum are the paintings of the Ukrainian artist Nikolai Getman. Getman was born in 1917 in the Ukrainian city of Kharkiv, a major city near the frontlines of the current Russian invasion. In 1945, not long after his discharge from the Red Army, he was arrested along with a small group of artists after one of them drew a mocking picture of Stalin on cigarette paper. Getman was sentenced to eight years in the Gulag (1945-53), which happen to be the same years served by Alexander Solzhenitsyn. (See this post for my reflections on his work.)

While Solzhenitsyn painted life in the Gulag with words, Getman painted it with an artist’s brush. After his release he produced 50 paintings of his experiences in the Soviet prison-camp system. He hid the paintings for decades, until they were finally revealed to the public in 1997 after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the Soviet Union and seven years before his death. (Here’s a short biography of Getman with many of his Gulag paintings.)

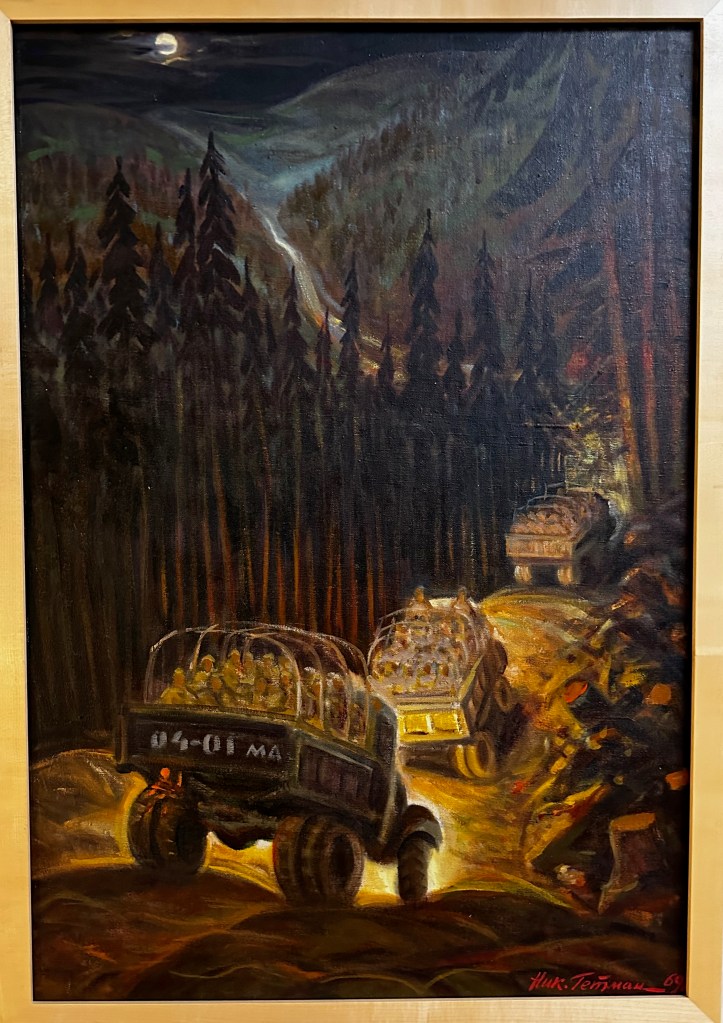

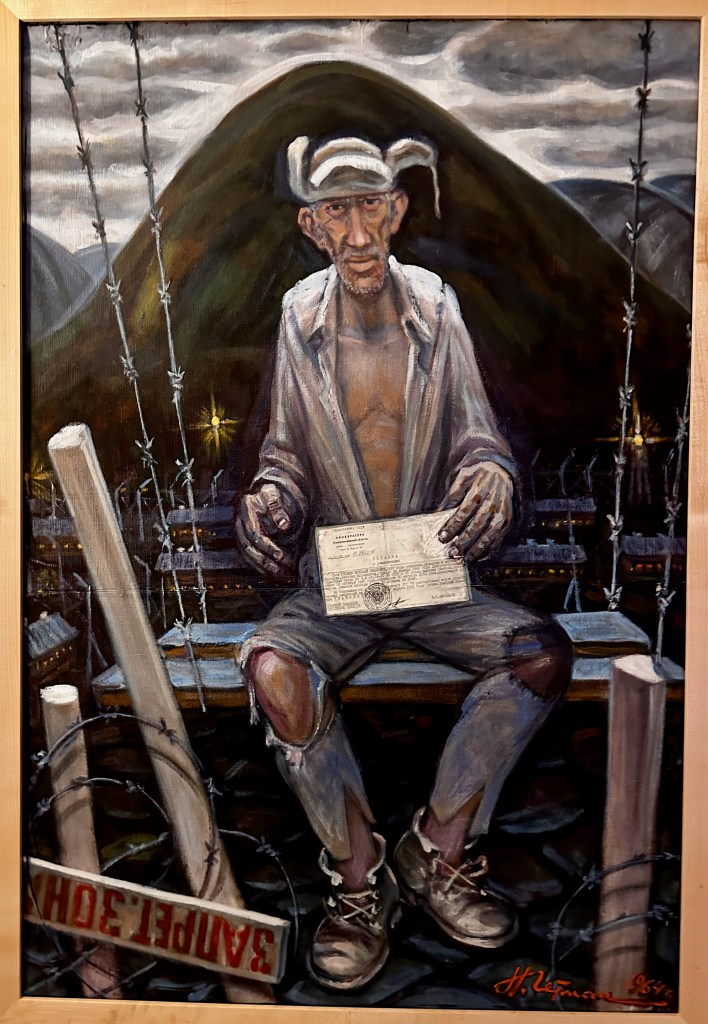

Below are three of the paintings that affected me the most, with the descriptions that were posted nearby:

“Headed for Kolyma,” 1969, Oil on canvas. “Prisoners being transported to forced labor camps often had to brave extreme elements without adequate food, water, or clothing. The uncovered vehicles for transportation made the journey unbearable and deadly in the freezing winters.”

“The Guards’ Kennel,” Oil on canvas. “Guard dogs, often fed more than the prisoners themselves, were trained to catch runaway workers. Getman believed that the way the Soviets trained dogs to be vicious killers reflected the mentality and inhumanity of the Gulag system.”

“Rehabilitated,” Oil on canvas. “Upon their ‘release,’ Gulag prisoners were often forced to live in certain permitted areas under heavy restrictions. After his release from the Gulag, Nikolai Getman endured for decades the stigma that prevailed in Soviet society against former prisoners. His rehabilitation letter is depicted in the hands of the prisoner in this painting.”

The young man at the museum’s reception desk told me that the museum draws a steady if modest flow of visitors each week, including school groups. I wish millions of my fellow Americans, especially the younger generations, could spend an our or two in the Victims of Communism Museum.

Like the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum located a mile south, the Victims of Communism Museum tells a story that is sadly relevant today.

Communism remains the ruling ideology in China, North Korea, Vietnam and Cuba. Xi Jinping, the party ruler in China, seems determined to turn China back to the days of Mao Zedong, whose murderous reign is recounted in the museum.

Vladimir Putin, the top dog in Russia, is no longer a professing communist, but he served the former Soviet Union faithfully for years. As the self-appointed ruler of Russia for life, he longs to restore what he sees as Russia’s past glory through the domination of its neighbors–currently Ukraine, but it’s easy to imagine Poland and the Baltic Republics coming into his cross hairs.

The museum makes it clear why the people of Ukraine are fighting so hard to resist the return of Russian domination. Ukraine suffered horribly under the Soviet government. In the 1930s, between 2 and 5 million of Nikolai Getman’s fellow Ukrainians were intentionally starved to death by Stalin and his minions in the Kremlin. In what Ukrainians call the Holodomor, Moscow forced collectivization on its farms, and when the people resisted, they confiscated their food to feed the army and export to other nations, while denying people the minimal food needed for survival. The result was mass starvation.

We live in a complicated world, and the U.S. government needs to deal with China and Russia in ways that promote our national interest and preserves the peace. But please spare us the moral dissonance of praising leaders who are the unapologetic heirs to those with the blood of 100 million people on their hands.