You may not have heard of Jimmy Lai, but he is the world’s most famous Catholic and former billionaire serving time in a Chinese prison for committing no other crime than peacefully defending freedom and democracy. With Pope Leo now in office, it’s my hope that the Vatican will take a more sympathetic interest in Lai’s plight than under the previous pontiff.

Jimmy Lai was born in Mainland China in the late 1940s, just as Mao Zedong and the communists took over the country. Lai escaped to nearby Hong Kong when he was about 12 and through pluck and hard work became a successful textile and clothing entrepreneur. He used his wealth in the 1990s to launch the popular Chinese-language Apple Daily newspaper, which combined aggressive journalism with a feisty editorial voice challenging the encroaching power of the communist authorities. He was arrested on trumped-up national security charges in 2020 and has been wrongly imprisoned since then.

Throughout his life, Lai has been an exponent of free markets and classical liberalism, with Milton Friedman and Friedrich Hayek as his intellectual guides. He became a serious Catholic later in life. Through his media outlets and his personal actions, Lai staunchly defended the civil freedoms of the people of Hong Kong. Those freedoms were supposed to be guaranteed for 50 years under the 1997 UK-China handover agreement, but they have been ruthlessly suppressed by the central government in Beijing since 2020.

You can learn more about Jimmy Lai by reading Mark L. Clifford’s excellent biography published last year, The Troublemaker: How Jimmy Lai Became a Billionaire, Hong Kong’s Greatest Dissident, and China’s Most Fear Critic (New York: Free Press, 2024). You can also view the well-done 73-minute documentary by the Acton Institute, “The Hong Konger: Jimmy Lai’s Extraordinary Struggle for Freedom,” available free on YouTube.

I pray regularly for Jimmy Lai. I pray that he would be released from prison, and until then that he would persevere and be a witness to his jailers. I learned from the book that he is not embittered or discouraged as he sits in isolated confinement. Lai sees himself as suffering on behalf of all those who sacrificed their lives in Tiananmen Square and who have given up their own freedom since then to defend the inherent rights of the Chinese people.

In an interview with Rev. Robert Sirico of the Acton Institute before he was arrested, Lai described the positive legacy of Great Britain’s 150-year colonial rule of Hong Kong:

We inherited Western culture and values and institutions. The British did not give us democracy, but they gave us rule of law, private property, freedom of speech, of assembly, of religion. This is why China is very afraid of us. The values we share with the West are very dangerous to Chinese in China. That’s why they want to clamp down on us. We are a small island but we have big ideas. (from The Troublemaker, p. 116)

Lai had the means and the opportunity to escape from Hong Kong before the crackdown, but he chose to stand with his fellow Hong Kongers and face the consequences. Clifford quotes Lai in the book on why he refused to flee:

A young prison guard asked me, when no one was around: “Why didn’t you leave before they arrested you, for surely everybody knew that it was coming to you?” “No, I could not leave, otherwise I could not raise my head and walk tall again. I must face the consequences of my actions, just or unjust. It is also a way to uphold the dignity of Hong Kong people, as one of the leaders for the fight of freedom. Also, if I shirk my responsibility and run away, I would be setting a very bad example for my children, [encouraging them to] run away from trouble and their responsibilities-indirectly I would destroy them. Besides while my colleagues and Apple Daily are holding the fort of press freedom and I run away from my responsibility, what kind of captain of the ship am I? No, there was no option for me but to face it.” (p. 190)

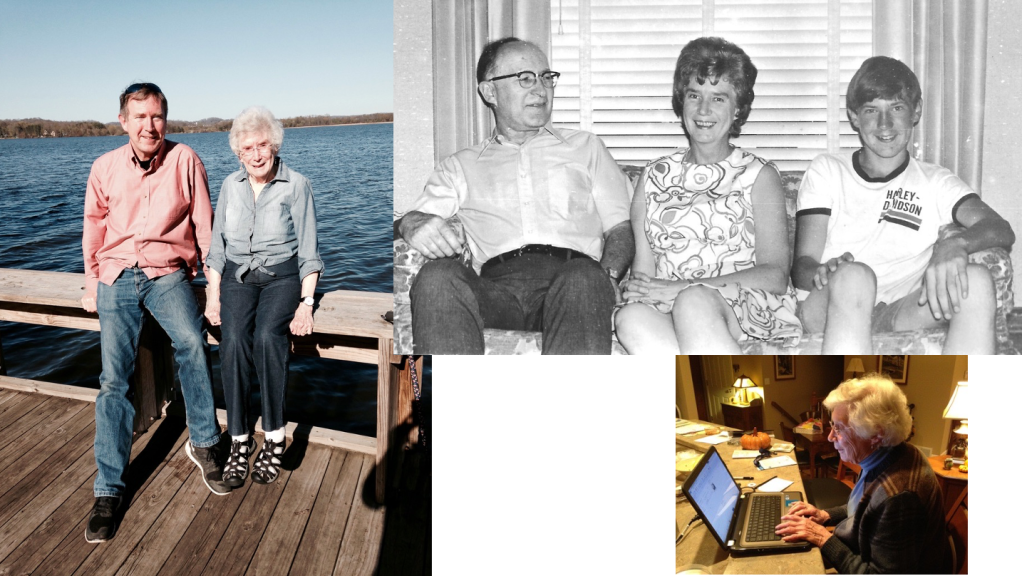

In my time at the Cato Institute in Washington, DC, I had the privilege of interacting in a tangential but meaningful way with Jimmy Lai and the Apple Daily staff. In 2000, during a visit to Hong Kong, I was invited to visit the Apple Daily headquarters by its opinion-page editor, Kin-ming Liu. I’d met Kin-ming before then when he visited the Cato offices. We naturally hit if off not only because of our libertarian leanings but because I had spent 12 years as an opinion-page editor myself at the Colorado Springs Gazette. (The photo shows us in front of the Apple Daily presses.)

After that visit I was asked occasionally to write articles for Apple Daily on US-China trade relations. Boxed away in my archives are a few treasured clippings of those articles as they appeared in the paper translated into Chinese. (Apple Daily was shut down permanently by the Mainland authorities in 2021.)

In a return trip to Hong Kong in December 2004, I was invited to Jimmy Lai’s home in Hong Kong to join him and a small group for lunch. Sometime before then I’d heard the story that one of Lai’s motivations to flee Mainland China for Hong Kong as a boy was his discovery of chocolate. (See the story below from Clifford’s book.) With this anecdote in mind, as I was getting ready to depart on my flight from Washington, I bought a chocolate figure of then US President George W. Bush as a gift. When I arrived at Lai’s house, I gave him the present as a token of friendship and a nod to his personal history. He was delighted, and I can still picture him eating a few pieces of the president’s bust after lunch with a contented look on his face!

Contrast that sunny memory to the reality today of Jimmy Lai sitting alone in his sparse prison cell. While I grieve for what has happened to Lai and pray for his release, the book made me see his confinement in a more positive light. In his faith and his love for the people of Hong Kong, Jimmy Lai has found meaning in his suffering. As his wife Teresa says of his time in prison: “He doesn’t see it as punishment. He is living in complete freedom.” (p. 211)

May all of us, including the new pope, never forget the unjust imprisonment of Jimmy Lai.

***

From The Troublemaker (pp. 16-17):

A bar of chocolate marked a turning point. One day, after carrying baggage for a disembarking passenger [at the Guangzhou train station], the man reached into his pocket and gave Lai a half-eaten Bar Six chocolate. Wrapped in foil with a bold orange paper wrapping, the Cadbury’s candy was unlike anything produced in China. Lai, feeling shy, turned away from the man to take a bite. “I was so hungry. It was so tasty. It was amazing. I turned and asked him ‘What is this?’ He said, ‘Chocolate.’ I said, ‘Where are you from?’ He said, ‘Hong Kong.’ I said, ‘Hong Kong must be heaven because I never tasted anything like that.’ That triggered my determination to go to Hong Kong.”

That taste of chocolate probably occurred in 1960, a year of famine in China. So desperate was the food shortage that Lai remembers grilled field mice as a delicacy he savored in those lean years. His childhood was marked by hunger and sadness. “The wound is deep and the scar is deeper,” he later wrote of his childhood. After he tasted the promise of another world, Lai begged his mother for permission to go to Hong Kong. “It took me a year to convince her.”