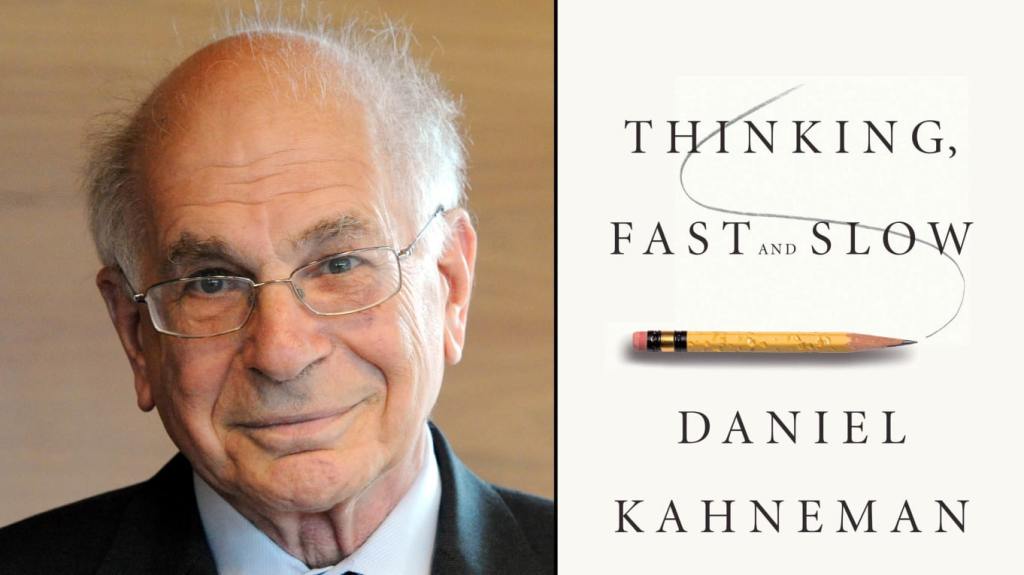

The behavioral economist Daniel Khaneman passed away at age 90 earlier this spring. I finally got around to reading his 2011 bestseller, Thinking, Fast and Slow, last fall and gained a lot of insight from it, both for my personal life and for public policy.

Most of us would consider it more of a compliment to be called a fast thinker than a slow one, but the book helped me understand that we often jump to conclusions too quickly when we should slow down and be more deliberate and methodical in how we make decisions. Our intuitions often lead us astray.

The core theme of the book is what Kahneman calls “a puzzling limitation of our mind: our excessive confidence in what we believe we know, and our apparent inability to acknowledge the full extent of our ignorance and the uncertainty of the world we live in. We are prone to overestimate how much we understand about the world and to underestimate the role of chance in events. Overconfidence is fed by the illusory certainty of hindsight” (p. 13).

This weakness in our human nature gives rise to the phenomenon we often observe in the public arena: that the less people actually know about a subject, the more confident they are in their opinions. (This even has a name: “the Dunning-Kruger effect.”) It explains why the much-derided experts can seem to hedge their opinions. It’s not that they are intentionally waffling, but that they can see better than most that particular circumstances can be complicated and nuanced.

“Paradoxically, it is easier to construct a coherent story when you know little, when there are fewer pieces to fit into the puzzle. Our comforting conviction that the world makes sense rests on a secure foundation: our almost unlimited ability to ignore our ignorance,” the author writes on p. 201. That’s something I need to remind myself of more often.

Kahneman argues that we would be better off, as individuals and as a society, it we relied more on statistical averages and algorithms rather than intuitive judgments. (The dictionary defines an algorithm as “a process or set of rules to be followed in calculations or other problem-solving operations, especially by a computer.”) Statistics can offer a base-line probability for assessing risk, a measure of real-world outcomes as opposed to our preconceived notions.

When we combine the broader frame of reference that statistics allow with an algorithm, we make better decisions. The author agrees with proponents of algorithms who “have argued strongly that it is unethical to rely on intuitive judgments for important decisions if an algorithm is available that will make fewer mistakes. …simple, statistical rules are superior to intuitive ‘clinical’ judgments” (pp. 229-30). To me, this all argues for using artificial intelligence to analyze problems and guide our decision making. No system is perfect, but relying on well-informed algorithms can help us avoid the pitfalls of our own distorted judgments.

Another weakness in our all-too-human judgments is that we tend to exaggerate low-probability outcomes, on the good side and the bad side. That means we can over-insure against risks that have a low enough probability that we could safely ignore them as a practical matter. It also means we tend to exaggerate our chances of winning the lottery. Both assumptions can cost us money and lost opportunities—as individuals and collectively.

Kahneman cites the jurist Cass Sunstein, who’s criticized the European Union’s “precautionary principle” as an example of over-weighting potential risks to society. A strict interpretation of the rule threatens to paralyze potentially beneficial innovations. Sunstein lists a number of accepted innovations that would not have passed the test if it had been enforced in the past, including “airplanes, air conditioning, antibiotics, automobiles, chlorine, the measles vaccine, open-heart surgery, radio, refrigeration, smallpox vaccine, and X-rays” (p. 351).

Kahneman’s insights have a lot of applications in day-to-day life. If you watch sports on TV, you’ve probably heard announces say a certain player who’s made a few shots in a row has a “hot hand.” But the author cites research that shows what we think is a pattern is really just a random variation. Steph Curry can nail five 3-pointers in a row, but that can be just as random as flipping a coin and having it come up heads five times in a row. The next flip (or shot) is no more likely to come up heads (or go in) than any of the last five. Khaneman writes that we “are consistently too quick to perceive order and causality in randomness” (p. 116).

[I tested this idea with a Python program that simulated a basketball player shooting dozens, hundreds, even thousands of shots in a row. If you program in a 40 percent chance of making a 3-point shot, and feed through randomly generated numbers, sure enough it will show the virtual player making five, six, seven shots in a row, but then missing a bunch in a row as well. The strings of makes and misses my program produced were neither hot nor cold, but just random.]

Kahneman applies this insight to the casino. We’re all too prone to the “Gambler’s fallacy,” the belief that after a long run of red on the roulette wheel, black is now “due.” In fact, the odds are still exactly the same. He writes: “Chance is commonly viewed as a self-correcting process in which a deviation in one direction induces a deviation in the opposite direction to restore the equilibrium. In fact, deviations are not ‘corrected’ as a chance process unfolds, they are merely diluted” (p. 422).

The book argues for “broad framing”— considering the total outcomes over multiple events, not just what might happen today. This is why we should buy high-deductible insurance, skip extended warranties, and not check our stock portfolio very often. Regarding stocks, the insights from the book argue for the “random walk” approach of owning a broad portfolio of stocks and holding them for the long run.

We tend to fear the loss of a certain amount more than we desire gaining the same amount—what Kahneman’s profession calls “loss aversion.” To get someone to risk losing $100 if a coin flip comes up tails, studies show you need to offer them at least $200 if it comes up heads. This is why an exhaustive study found that “professional golfers putt more accurately for par than for a birdie” (p. 300). The pain of a bogey outweighs the pleasure of birdie. It’s why consumers will accept a cash discount at the gas station but will rebel at a credit-card surcharge, even if the outcome is the same.

I could go on about the insights from this book. It made me think more deeply and I hope more slowly and methodically about the decisions I make every day. May I be more humble in my judgments as I try to make sense of this complex world we live in.

Surprised to know that you can apply Python very well. I think that I will keep learning that later to follow your footstep “as a student of social science”, Sir.